Baking Powder

What is Baking Powder? How do we get it and what does it really do?

Baking Powder has always been a rather mysterious ingredient to me. Baking is a controlled chemistry experiment in your home. Like Rachel Ray, I am not a great baker because I rarely measure things so precisely (I leave that department to my wife, Chaya). While the “little of this, little of that” method works great for sauces or stir fries, it is wildly unpredictable for something as precise as baking where ingredients are weighed by the pros not measured by volume.

We happen to have three very dedicated fans of Pooh Bear in our house, and I cannot tell you how many times we have read the story, “Honey of a Cake” to them. In case you are not as conversant in the adventures of the Hundred Acre Woods I will bring you up to speed on the story, Rabbit wanted to bake a cake and Pooh, Tigger and Piglet wanted to “help.” Rabbit gives the advice that every baker would give a novice: the recipe is to be followed exactly or else you run the risk of ruining it. As you may have guessed, this controlled chemistry experiment in Rabbit’s kitchen goes awry when Rabbit turns his back after dispensing the bit of knowledge to the group that the baking powder helps the cake to rise and become bigger. Well, if a little cake is good then more cake must be better, right? The story ends with a huge mess that the foursome has to eat their way out of, but it shows the power of this unassuming chemical leavener.

For millennia bakers knew of two ways to leaven (or create a rise in) a baked product: yeast or elbow grease. Yeast is the natural way of getting a rise in a baked product as this single-cell fungus digests the sugar it releases carbon dioxide (see Chaya’s great blog on yeast). The trouble with yeast is that it takes awhile to work (after you proof it) and when you are in the mood for cake you probably do not want to wait that long. Alternatively you could have a batter with a high egg content and vigorously whip it to introduce air bubbles into the batter.

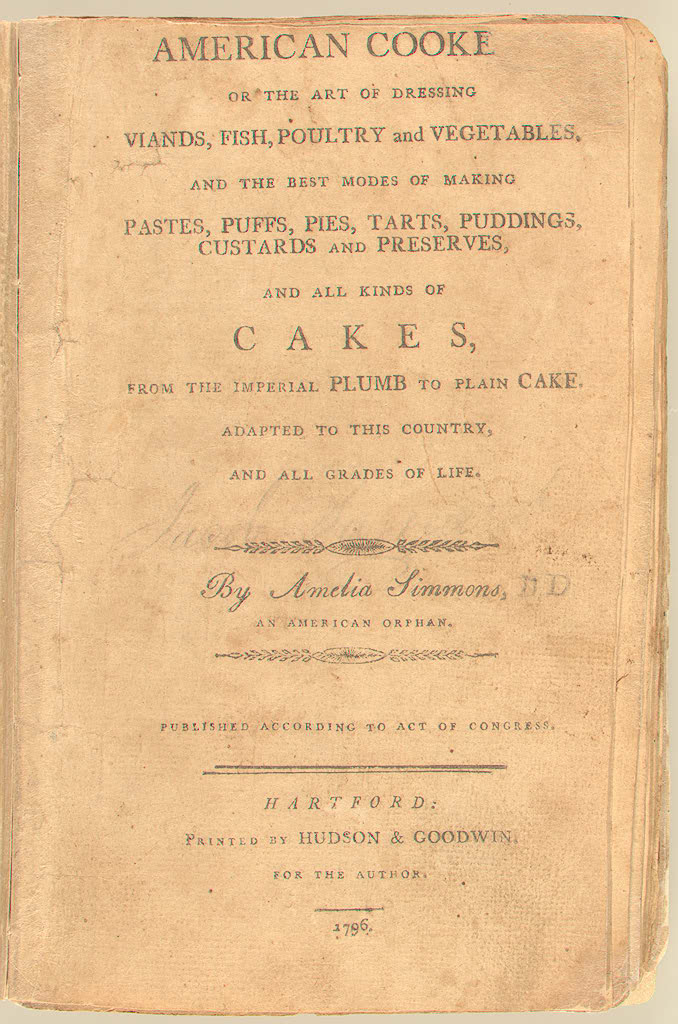

The use of a chemical leavener seems to be uniquely attributed to the (perhaps accidental) success of early American bakers. America’s first cookbook written by Amelia Simmons titled, American Cookery (you can preview it here from the LoC) is the earliest written source known to call for a substance known as “pearlash.” Pearlash (Potassium Carbonate) is the refined residue that is reclaimed from wood ashes (potash) which was known to be used to make lye for soap, but the possibilities for it to be used for baking were pretty novel. “Recipes for cake-like gingerbread are the first known to recommend the use of pearl ash [sic], the forerunner of baking powder” (Library of Congress).

The U.S. Patent Office granted only three patents in 1790, its first year of existence. . . . One concerned the manufacture of pearlash, the precursor of baking powder, and the other was for automated flour-milling machinery, which led to the fine white flour. Both are evidence of the importance of our cultural drive for improved cake baking (Ettlinger, 2007).

The Potassium Carbonate in the ingredient pearlash was a strong alkali thus releasing carbon dioxide (when it reacts with an acid) into the dough thus leavening the final product. Today we depend on a more reliable alkali called sodium bicarbonate (baking soda)—more on that in Part 2. The problem was that pearlash was great for gunpowder, soap or glass making, but largely unpredictable to bakers with its potency or timing of effect—baking, after all, is an exact science. A better method needed to be devised because acids were also either unpredictable or hard to come by i.e. sour milk, lemon juice, vinegar or cream of tartar (Ettlinger, 2007). A more predictable, shelf stable acidic source was needed that could be shipped to the baker and used on demand.

What is baking powder? “Baking powder is a crystalline powder that combines baking soda with dry acidic ingredients that react when water is added, plus cornstarch to prevent clumping and to control the amount of gas produced per unit of baking powder” (Joachim & Schloss, 2008). So what are these dry acidic ingredients that made Rabbit’s cake expand beyond belief? To answer that, we need to go back to Eben Norton Horsford, a Harvard chemistry professor from 1847 to 1863. As with many American inventors, Horsford’s life was rather interesting. He was formally trained as a civil engineer in his home state of New York. He wanted to marry, but his fiancée’s father would not approve until he was more established—so he set out to Germany for further scientific study. It was there that the fortune would change for the man who eventually authored, The Theory and Art of Bread-making, A New Process without the Use of Ferment.

Horsford spent two years in Giessen, studying the nutritive value — including the protein content — of various grains among other topics in organic chemistry. . . . In any event, while in Germany, he was nominated for the Rumford chair at Harvard University. This academic post had been established by Count Rumford, an inventor and entrepreneur. With the strong support of Liebig and his old mentor Webster, Horsford was formally offered the professorship in February 1847, with an annual salary of $1,500 (American Chemical Society, 2007).

How did Eben Horsford help the plight of bakers worldwide? What is monocalcium phosphate (MCP)? Read Part 2 and we will wrap up this very interesting story of baking powder. Here is a hint:

Wilson

Pro Deo et Patria

Works Cited:

Library of Congress. (n.d.). Amelia simmons, american cookery (1796). Retrieved from http://myloc.gov/Exhibitions/books-that-shaped-america/1750-1800/ExhibitObjects/American-Cookery.aspx

Ettlinger, S. (2007). Twinkie, deconstructed, my journey to discover how the ingredients found in processed foods are grown, mined (yes, mined), and manipulated into what a. (First printing,March 2007 ed., Vol. 1, p. 136). London: Hudson st Pr.

Ibid.

Joachim, D., & Schloss, A. (2008). The science of good food. (p. 121). Toronto: Robert Rose.

American Chemical Society. (2007). Eben horsford. Retrieved from http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/bakingpowder/horsford.html

Photo Credits:

Simmons, A. (1796). American cookery. (p. Cover). Hartford: Hudson & Goodwin. Retrieved from http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/treasures/images/uc006181.jpg

Rumford Baking Powder from Clabber Girl: http://www.clabbergirl.com/consumer/products/rumford/

Additional Resources:

Recipe for Challah Bread that shows vigorous kneading: http://www.cookstr.com/recipes/basic-challah-dough

Recipe for Sourdough that also calls for vigorous kneading: http://www.instructables.com/id/No-Sourdough-Buttermilk-Easytastybread/step3/Because-I-knead-the-dough/

Another great baking blogpost on the early uses of pearlash: http://www.fourpoundsflour.com/the-history-dish-pearlash-the-first-chemical-leavening/

Biography of the life of Count Rumford: http://acswebcontent.acs.org/landmarks/bakingpowder/count.html

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.