As a family, we (mostly) follow a traditional foods diet. Living in Montana, we are somewhat meat-heavy in our diet (no apologies—we are far healthier than ever before). We are busy, and being a bread baker I often look to the quick sandwich to feed my family while on the go.

I am going to smash the excuse that real food costs more, or that you do not have any choices. I have already done the hard work (out of necessity for my family’s health) of pricing out each option ounce-for-ounce and I am going to pass along my “aha moment” to you.

The Local Deli Counter

I asked the lady if I could see the ingredients list for the cold cuts on sale. No verbal answer, but she stared at me with that look on her face that said, “It’s meat. Meat.” The manager understood my plight thankfully, and said, “If you cannot have dextrose or cornstarch, we might not have any deli meat for you.” Label by label by label, we tediously discovered that ultimately, the delicatessen is off-limits. We discovered that there is one “safe” and cornless deli meat, pastrami, which probably isn’t “safe” at all by other standards. On that particular day, I was just trying to feed my kid on a busy trip into town so I bought it (crazy expensive too, I might add).

I blame a lot of my “lack of real food choices” on the fact that I live in a small town, but I found that is not true. On a recent trip to an extremely metropolitan East Coast city, I found the local deli still had only a single non-corn meat…pastrami. They also had the incredulous look of “It’s meat, Lady” on their faces, and the “safe” choice still had an ingredients list at least 5 items long.

The Solution

Finding pre-sliced lunch meat without all of the corn syrup, msg, food coloring, preservatives, and other unnamed gunk…it can be done but not easily or cheaply. We have yet to discuss what the animal was fed, it’s living conditions, the use of antibiotics, or genetic modification! Lest you feel like giving up before you start, there is a solution that only takes minutes of your day—less if you plan ahead.

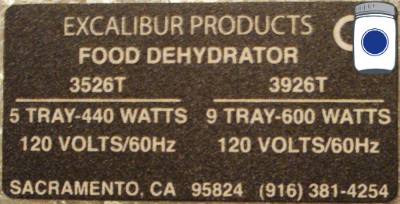

My solution was the food slicer (currently $20 off in honor of this blog). Originally purchased for making our 6-8 gallons of yearly sauerkraut, we find reasons to use it all of the time. In fact, we find it really helps to make fermented foods like pickles, sauerkraut, and kimchi simpler and thereby, we have increased our intake of those naturally probiotic foods. I probably use it every bit as often as a companion to my Excalibur dehydrator…zucchini chips, tomatoes, onions, carrots, potatoes…you get the idea. But back to the meat of the matter.

I have control over the meat we are eating. We get our pork semi-locally (2 hours away, and in Montana that is “local”); they even deliver it twice a year. Grass-fed, no hormones, humanely butchered, and unlike any other pork I have ever eaten in my life. Try to find those options in your community.

For comparison’s sake, I will be talking only of ham so that we have a baseline.

Option 1: The Local Producer

Very often, your local producer is using locally-grown feed. You can usually go to the farm yourself to see the condition of the livestock. You can ask questions, walk around, smell the roses (so to speak). There are generally different package deals; if you have adequate freezer space you can even buy ½ an animal, or a whole animal. Find someone else to split the meat with to get the best deal of all.

If I buy just a ham a la carte, it will cost $7.49/ lb. That’s 47¢ an ounce. A bit too high, but if I buy in bulk, I can bring that cost all the way down to 19¢ an ounce! As an aside, our local producer will sell sliced ham to you for $1.50 more per pound. That food slicer is paying for itself.

Option 2: The Wholesale Box Store

I recently talked to a friend who lives in the Washington DC area who said that the Costco/Sam’s Club style store is the “only way we can stay within a food budget around here”. I know that this is a common way to shop, and so here was my price comparison.

25¢/oz. for this smoked ham, cured 4-6 months. No information whatsoever was given about the farm, farming methods, antibiotics, feed, animal treatment, and so on. The ingredients list was acceptable (salt, sugar, pepper, that type of thing).

Option 3: The Local Health Food Grocery Store

Having recently emptied my bi-annual supply of pork, I purchased this one at a large, full-selection health food store. I was pleased with the ingredients (the lack thereof), the flavor is delicious, and I know that this is a quick, safe meal for a family on-the-go. I sliced the whole thing and put most of it into the freezer for another day.

39¢ an ounce. Your health food store might be cheaper—we live in a food-expensive area because everything must get trucked in over the mountains.

Conclusion

Plan a family trip out to your local farm (use Farmmatch, Local Harvest, or Farmplate to find one). Make a day of it, have an experience and reconnect with your food. Then the next day, slice up your meat and put it all into your freezer for later convenience.

Oh, and as an aside—here is the ingredients list for a Hillshire Farm product, very typical of everything out there.

Thick Sliced Virginia Brand Ham

Water Added, Caramel Colored ● Made in Kentucky

Ingredients:

CURED WITH WATER, SUGAR, DEXTROSE, CONTAINS 2% OR LESS OF: SODIUM LACTATE, SALT, SODIUM PHOSPHATE, CLOVE, SODIUM DIACETATE, SODIUM ERYTHORBATE, SODIUM NITRITE, CARAMEL COLOR.

Don’t forget to make a panini for me,

Chaya

P.S.– The Nesco food slicer is $20 off right now! No coupon needed; we just want to encourage you to produce, prepare, & preserve–your own lunch meat!

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance

All other pictures are property of Pantry Paratus. Feel free to pin or share the photos as long as you give proper attribution. Thank you.