Chocolate, Part II

The Science (and Art) of How It Is Made

The Bean

Theobroma cacao is a hardy plant that does well under jungle canopy shade in a consistently warm climate not subject to freezing, and it grows well with a wide variation of rainfall and soil conditions (Hebbar, p. 4-5). Temperature is its biggest limitation, which shatters my dreams of one day cultivating the glorious plant for myself here in Montana. For this reason, most cacao plantations are located near the equator in a sort of “chocolate belt” with the world leader in production being the Ivory Coast (Cote d’Ivoire) followed by Brazil. Chocolate gives the term “cash crop” new meaning with the world total production higher than 4.1 million tons!

Over the ages and in different parts of the globe, various comestibles [items of food] have been hailed as the food of the gods: honey, truffles, hallucinogenic mushrooms, wine. None more so, however, than chocolate, if names are anything to go by. For the fragrant, dark brown substance many people around the world feel they could hardly live without derives from a plant whose official botanical appellation is Theobroma cacao: Theo = gods; broma = food (Bardi & Pietersen, p.13).

The cacao beans are wrapped in a most unusual package. “The seeds are encased in a large colorful pod . . . The large pod is green while maturing and turns yellow, orange, red or purple when ripe. The pods vary significantly in size, shape and texture. They range from about 10 cm to greater than 40 cm in length! They have 5 to 10 veins or longitudinal ridges and are spherical to oblong, shaped roughly like an American football (N/A, 2002).” These seeds nest along the wall of the pod and, along with the pink fleshy fruit, are described as being somewhat like a loose apple texture and mango flavor—if I ever get the chance to try one, I will certainly report back.

Fermentation

Your apples come straight from the tree; your chocolate does not. Somewhere along the way, it was discovered that the slimy, fermented pods were desired and not the fresh seeds. I do not know who initially thought that was an appetizing idea, but we are all glad for the discovery.

There are anywhere between 20-40 beans inside of each pod. Once they are removed by hand, they are spread out for fermentation; this does not just change the color from white to brownish red, it always changes the flavor significantly. The “how” of the fermentation relies very heavily on local traditions. The beans ferment for approximately one week—any longer and the risk of germination increases, which will ruin the flavor. Naturally occurring bacteria and enzymes do the job on larger batches, but on the smaller batches, it is common to add some yeast to ensure a quick start on the fermentation process (Hebbar, p. 13). Once fermentation is complete (evidenced by the color and flavor), the seeds must be rinsed; this is generally the last process on the plantation or farm where the Theobroma cacao plants are grown.

Grinding & Roasting

Once the beans arrive to the chocolate factory, they are cleaned, sorted, and then roasted whole between temperatures of 210-250˚F depending on the end use of the product (Bardi, & Pietersen, p. 20). When the shells are later removed, you are left with a “nib”, a small, cracked kernel fragment. You can think of this as the “meat” of the bean, if you will. When these are melted, you have “chocolate liquor”. This is the start of something really good.

Cocoa Butter

The cacao seed is over 50% vegetable fat, what we call cocoa butter (McMahon, p. 58). This is a naturally-emulsified oil with a low melting point close to that of the temperature in a human mouth, and so the butter itself has many various applications including candy, lotion, and medicines. This oil must be (mostly) removed for powdered chocolate, which is down through a series of huge hydraulic presses that push this yellow fluid from the chocolate liquor (McMahon, p. 69). Couverture is chocolate that has extra cocoa butterfat added to it, used extensively by candy makers and chocolatiers for coating and dipping.

This is where art and science collide. Listen to this world-renouned chocolatier explain how the source of chocolate and the source of inspiration become delicious (and beautiful, too):

Melting In Your Mouth

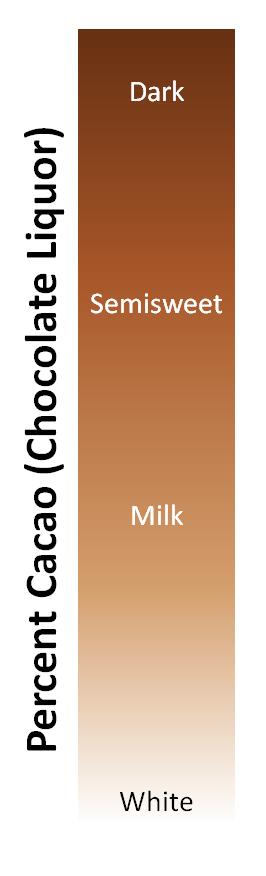

Once you have the chocolate liquor, you have the raw ingredient for a never-ending surplus of indulgences. Dark chocolate, milk chocolate, bars, powders, candies, drinks…what is added to the liquor and how it is molded and packaged, well…let us just say that we all have our own preferences. Personally? I say go dark or go home.

Bittersweet Chocolate (70% cacao or more) has the most chocolate liquor and the most intense chocolate flavor. Look for bitter, roasted, fruit, earthy, woodsy and/or nutty notes.

Semisweet Chocolate (50% to 65% cacao) has a strong chocolate flavor with a good balance of sugar: it is not too sweet and the aftertaste is equally balanced.

Milk Chocolate (30% to 45% cacao) is milder and sweeter because it is made with milk and a higher sugar content than the darker varieties. It also has a smaller quantity of chocolate liquor and, therefore, fewer flavors and aromas. Look for brown sugar, milk, cream, cocoa, vanilla, honey, caramel, nutty and/or malt flavors.

White Chocolate (0% cacao) has no chocolate liquor. Previously, by FDA regulation it wasn’t considered to be chocolate but its own entity. While white chocolate lacks chocolate liquor, it includes the milk and vanilla used in milk chocolate. These ingredients give it a variety of sweet flavor notes, including cream, milk, honey, vanilla, caramel and/or fruit.

(Rot & Hochman, 2009)

No matter your preference on flavor, keep in mind that the ethical side of harvesting—although a world away—really matters. Also remember that the ingredient additions also matter for your long-term health. Enjoy this antioxidant and natural-fat food without guilt by knowing that you are purchasing an ethically harvested, natural product.

Bon Appétit,

Chaya & Wilson

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.

Sources:

Bardi , & Pietersen, (2006). The golden book of chocolate. Florence: McRae Books.

Hebbar, P., H.C. Bittenbender, and D. O’Doherty. 2011 (revised). Farm and Forestry Production and Marketing Profile for Cacao (Theobroma cacao). In: Elevitch, C.R. (ed.). Specialty Crops for Pacific Island Agroforestry. Permanent Agriculture Resources (PAR), Holualoa, Hawai‘i. http://agroforestry.net/scps

McMahon, J. J. (1998). Built on chocolate: The story of the Hershey Chocolate Company. Los Angeles: General Publishing Group.

N/A. (2002, September). Xocoatl. Retrieved from http://www.xocoatl.org/tree.htm

Teubner, C. (1997). The chocolate bible. New York: Penguin Studio.

Rot, P., & Hochman, K. (2009, July). The flavor & aroma of chocolate a guide to understanding the world’s finest chocolate. Retrieved from http://www.thenibble.com/REVIEWS

Photo Credits:

Conrad Fernandez, Cacau Plantation. Sourced at: http://epod.usra.edu/blog/2010/04/cocoa-plantation.html

Chocolate plant (Cacao Pods) & cacao drying both sourced at: http://www.bigisland-bigisland.com/Hawaiian-Chocolate.html

Cocoa Plantation was taken by the Richards family, missionaries to an island near Fiji. Learn about the family’s work here. The photo was sourced at: http://richardsroad.blogspot.com/2010_10_01_archive.html