Classifications of Bread

A systematic approach to the staff of life

“Bread is basic. Most likely it was the original baked good, for at heart bread is nothing more than flour and water” (Joachim & Schloss, p. 64).

People think in concepts that are reduced to words such as: tree, house or bread. What is crystal clear in one person’s head may not be so to another person, so language was invented to trade these ideas in the form of words. And when a particular kind of tree is under discussion, not just any old word will do and so descriptors were invented to classify things and identify their distinctions—bread is one such thing. What comes to mind as “bread” in France is different than New Zealand, China or Argentina because everyone has their own favorite kind of bread depending on available ingredients and techniques. So it is good that people (who like to name things) have thought of a way to have different classifications of bread.

Bread is largely divided up by its contents with one exception being flat bread which is a label applied to the physical characteristic of the bread namely its height. Peter Reinhart in his landmark book, The Bread Baker’s Apprentice, lists five different criteria in which bread is classified, namely:

![]() Hydration

Hydration

![]() Richness

Richness

![]() Pre-fermentation

Pre-fermentation

![]() Leavener

Leavener

![]() Height (as in flat bread)

Height (as in flat bread)

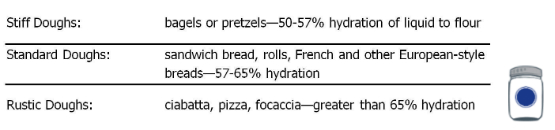

First up, classification by hydration: Bread’s basic ingredients are flour made from some kind of grain and water; from there you can do just about anything to vary the staff of life—everything from whole food to the now defunct Wonder Bread. Delineating bread by water content is an example of a pretty straight forward application of Baking Math. According to Reinhart, the types are stiff doughs, standard doughs and rustic doughs (Reinhart, p. 45).

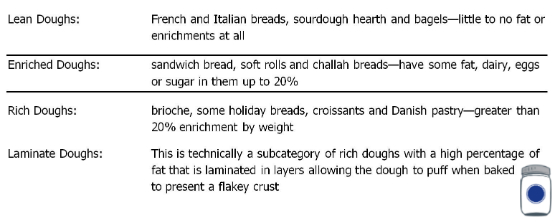

Next is the Classification by Richness. Flour and water are the basic ingredients for both paper mache and a genuine Valley Forge soldier’s firecake—neither of which tastes very good at all. So over the past few millennia man has engineered bread to taste moister, absorb more gravy or just feel better to the mouth by enriching it with fats, milk and/or sugars (whenever available). Reinhart identifies three kinds of these doughs: lean doughs, enriched doughs and rich doughs with a subcategory called laminate doughs (Reinhart, p. 45).

Classification by (the use of) Pre-fermentation is also another category by itself. This is the means to make bread extraordinary through the careful manipulation of time, enzymes and the raw fuel found in grains.

As dough ferments, its yeast continues to produce carbon dioxide, which filters into the air pockets formed by kneading, causing them to inflate and raise the dough. The gentle stretching continues to develop the gluten, so even barely kneaded dough will become stretchier and more cohesive during fermentation. Yeasts reach their greatest activity at around 95˚F (35˚C), so at that temperature a dough will rise rapidly, but a fast-rising dough can also develop unpleasant yeasty aromas and an abundance of unwanted by-products of yeast metabolism, like alcohol. Lowering the temperature, by letting the dough rise in a cool room or in the fridge, extends the rise, diminishes off flavors, and encourages more desirable flavors. The longer a dough ferments the more time there is for yeasts and bacteria in the dough to generate flavor compounds. This is most evident in whole wheat breads, in which a slow rising increase the nutty and honey-like flavors in the grain (Joachim & Schloss, p. 66).

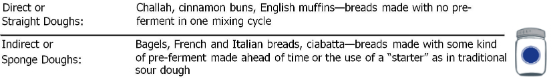

The topic of pre-fermentation is a fascinating one, and we will have a whole blog dedicated to that next week. For now, suffice to say that the two categories that Reinhart identifies regarding pre-fermentation are straight doughs and indirect or sponge doughs (Reinhart, p. 45).

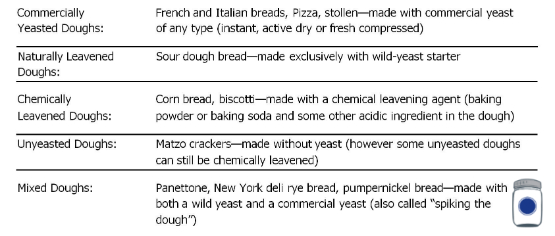

Then we have classification by leavener. The type and use of (or lack thereof) regarding leavening agents is how this category is divided. Breads here can be commercially yeasted, naturally leavened breads (wild yeast or sour dough), a hybrid of the above (also called “spiking the dough”) and unyeasted doughs that may or may not be chemically leavened (Reinhart, pp. 45-46).

Lastly we have the classification by height. Where all of the other categories up until now have been groupings of breads by ingredients, this last category is a bit of a catch-all. Flat breads can be enriched or lean, yeasted or unyeasted and are all differentiated from other breads by their low height. Both pizza and matzo crackers are included here in flat bread, while the former has yeast and is enriched the later does not have yeast and is lean. (Reinhart, p. 45).

With these classifications you can catalog any bread. Take Chaya’s awesome bread recipe, it scores as follows: stiff, enriched, direct and commercially yeasted which helps explain it looks like a pirate boarding party with butter knives in hand when the bread comes out of the oven. If you do not own Reinhart’s book, you can click on this link to see a view of pages 46-47 to look up a bread by name and see what its classification is. Bread baking is a controlled chemistry experiment, and when you learn what the classifications of bread are you will better understand how to bake it or better yet, how to make substitutions when necessary (or trouble shoot when something goes wrong). Bread, with thousands of recipes, there is likely a loaf of bread awaiting you at the end of the learning curve. Are you are a bread baking pro? Then try different ferment techniques to really give that flavor some kick! Enriched or lean, good home baked bread is tough to beat, so leave a comment and tell us how yours comes out!

Wilson

Pro Deo et Patria

Photo Credits:

All photos by Pantry Paratus

Tables are adapted from Peter Reinhart’s book, cited above

Works cited:

Joachim, D., & Schloss, A. (2008). The science of good food. (p. 64). Toronto: Robert Rose.

Reinhart, P. (2001). The bread baker’s apprentice: mastering the art of extraordinary bread. (p. 45). Berkeley: 10 Speed Press.

Further Reading:

https://www.stellaculinary.com/scs20

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.