Pre-ferments: How They Work

Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a yeast by any other name

The eyes in swiss cheese and the pockets in French Bread are both caused by trapped gasses—however the first is caused by bacteria (Monera Kingdom) and the second is from yeast (Fungi Kingdom). In bread, it is possible to leverage both through the use of pre-ferments.

If you read our other blogs on pre-ferments you are likely sold on them and you are already on your way to making great bread. I just wanted to fill you in on a bit of the “how it works” behind the scenes with the smallest parts of nature doing all the heavy lifting. Enzymes do so much for us and eventually to us. Need to make cheese? Enzymes can help you do that. After I am put in the ground one day to make compost, it will be enzymes doing the hard part of converting me to soil. Hand-in-hand with enzymes, are bacteria recycling everything in nature.

Enzymes typically end in “-ase” and are named for the sugar that they consume which typically ends in “-ose.” For example, amylase is the enzyme that converts the sugar in a bruised or freshly cut apple to the brown color we observe. The amylase enzyme is acting on the amylose sugars in the apple, of which fructose is one kind of amylose. “Enzymes are complex proteins that act as catalysts in almost every biochemical process that takes place in the body. Their activity depends on the presence of adequate vitamins and minerals, particularly magnesium” (Fallon & Enig, p. 46). Great, but what does that have to do with bread?

An enzyme is what nature uses to break stuff down, whether they are working in your saliva or in huge vats in a Cargill plant in Blair, Nebraska turning long chain corn sugar into short chain high fructose corn syrup—enzymes reduce things. Typically we would not want to leverage this if it were fruit salad, so we counteract enzymes with acids. However, in creating a great pre-ferment we are cheering the enzyme process as it is the first step in releasing the grain’s full potential.

Here is an experiment that you can try at home: take a pinch of flour and put it on your tongue—it likely does not taste palatable at all, why is that? “Flour tastes like sawdust because its sugar components are too complex to differentiate on the tongue” (Reinhart, p. 59). The tongue is not set up to taste let along fully appreciate the wheat berry or its flour in its raw state because the sugar chains are way too long. This is why sprouted bread has markedly higher nutrition, because the enzymes have already done so much of the work to make the nutrients available.

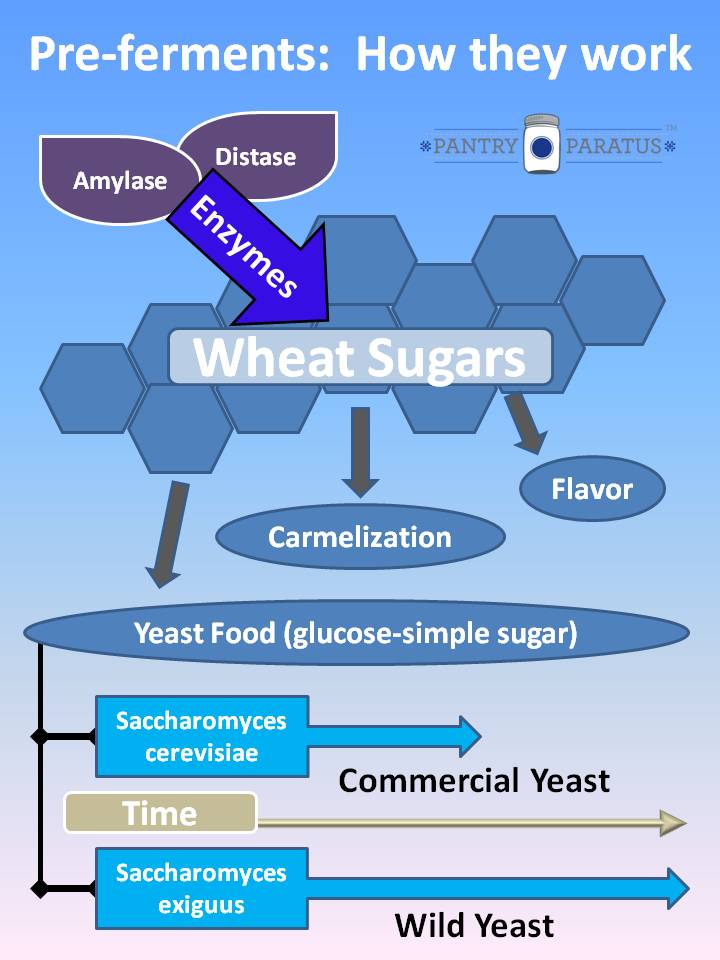

So the bread baker will either use the natural enzymes present in the dough plus time or he/she may wish to add a small percentage (usually .5-1% by weight) of an enzyme such as malted barley to the dough. The enzyme process will break down the wheat sugars, this much you know, but the follow on processes are what makes bread truly extraordinary. According to Reinhart, amylase and distase break down the wheat sugars to impart three subsequent effects: color (called “carmelization” by bakers) for the crust and crumb, flavor (the whole reason we are doing this!) and food for the yeast.

There are enough enzymes naturally occurring in flour that it is not always necessary to add them in the form of malted barley, as long as you are able to stretch time long enough to allow them to do their job. This is, in a nutshell, why pre-ferments create superior bread: they are a way to manipulate time, to stretch it, so that the wondrous chemical activity going on at the cellular level can fulfill its mission (Reinhart, p. 64).

Hmmmmm, food for the yeast? I thought that is why we added enrichments to the bread? You certainly can do that, but in Europe luxuries such as sweeteners were not always available, so pre-ferments were leveraged to embody flavor and develop structure in the bread. Yeast is a simple organism, a fungus, an eukaryotic microorganism to be exact, and it eats simple sugars like glucose.

But not all yeast is the same, nor does it have the same efficacy. Reinhart, who prefers instant yeast, gives the following equivalency chart for substituting yeast (p. 60):

100% fresh yeast = 40-50% active dry yeast = 33% instant yeast

Typically all yeast that we buy will be the commercial yeast known as Saccharomyces cerevisiae otherwise known as baker’s yeast or brewer’s yeast—it is the same thing. Breaking the word down we get from Latin: Saccaro, meaning “sugar,” myces, meaning “fungus,” and cerevisiae, meaning “beer.” We can otherwise say that as: “sweet fungus of beer” (Volk & Galbraith). This yeast is produced to be reliable and predictable for baking—two things that you definitely want. Pre-ferments using this kind of yeast are easy to work with and have reproducible results.

The other kind of yeast you really do not need to buy, because it is everywhere. It is the white powdery residue on the wheat berry, a grape or even a plum—yes, we are talking about wild yeast or Saccharomyces exiguus. This is typically used in sourdough breads, and the wild yeast works in conjunction with bacteria, notably our old friend Lactobacillus.

The complex sour flavor is not created by the wild yeast [alone]. Other bacterial organisms, specifically lactobacillus [sic] and acetobacillus [sic], create lactic and acetic acids as they feed off the enzyme-released sugars in the dough, and these are responsible for the sour flavor (Reinhart, 65).

Remember that we are leveraging time in this process as well, so here is where the road splits off the direct doughs from the indirect doughs (using pre-ferments). I have friends that are beer brewers and they say that everything has to be spotlessly clean because any bacteria will ruin a batch of beer. “If bacterial activity creates too much acid, this type of yeast will die and make the bread taste funny, with an ammonia like aftertaste and a weakened gluten structure caused by the glutathione released by the yeast. Most regular Saccharomyces cerevisiae leavened breads have a pH level of 5.0 to 5.5” (Reinhart, 66).

On the decidedly more acidic end of the pH scale is Saccharomyces exiguus which works best in a pH level of 3.5 to 4.0 “and therefore thrives when the bacteria does its work creating lactic and acetic acids. Since it takes twice as long for the bacteria to create flavor as it takes for the yeast to leaven the dough, it requires a hearty strain of yeast to endure” (Reinhart, 65). This chart should sum up everything we talked about so far:

If you have a recipe, tip or trick for using a pre-ferment—please leave a comment and share it with us. Also, if you are a US resident, and you are over 18 and you have entered a valid e-mail address—I have a small prize for the first person who posts what a “barm” is in the comment section below (without doing an internet search, please).

Wilson

Pro Deo et Patria

Works Cited:

Fallon, S., & Enig, M. (2005). Nourishing traditions. (Deluxe Edition ed., p. 4). Washington DC: NewTrends Publishing.

Reinhart, P. (2002). The bread baker’s apprentice, mastering the art of extraordinary bread. (p. 27). Ten Speed Pr.

Volk, T., & Galbraith, A. (n.d.). Retrieved from http://botit.botany.wisc.edu/toms_fungi/dec2002.html

Photo Credits:

Saccharomyces cerevisiae by photo credit: Rising Damp via photopin cc

Yeast and saccharomyces exiguus are taken from the Public Domain

All other photos and graphic by Pantry Paratus and may be used with permission with proper attribution–thanks.

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.