Baking Math

The tastiest way to learn more about Baker’s math

Endeavoring to understand Total Flour Weight

When I married Chaya, that changed my life. When I read The Bread Baker’s Apprentice by Peter Reinhart and that changed my outlook on baking forever. Is baking bread an art or science? Likely it is both. But for anything to be called a science it has to be observable, measurable and in certain cases reproducible (no one gets reproduce creation or the Roman Empire for example, but we can sure study the heck out of them). In that regard professional bakers rely on the measurements they use to be precise in the controlled chemistry experiment we call baking. To pull all this off, bakers have developed baking math or baker’s math to get a reliable yield from batch to batch.

The problem: Not everyone has the same definition for the universal English unit of measurement we refer to as “the cup.” One cup of flour (by volume) that I measure might be more than one cup of flour that Chaya would measure, so the dough made with those units of flour would perform differently as well. To mitigate this, baking math starts with weighing the ingredients not measuring them by volume.

1 cup of flour scooped by one person may not weigh the same as 1 cup scooped by another. That is why professional bakers prefer to use weights, since 1 pound of flour, regardless of how many scoops or cups it took to get there, will weigh the same 1 pound from person to person (Reinhart, p. 27).

So when you talk about baking math or any kind of math it leads to proofs (proof of concept and not proofing dough in this particular instance). So I set out to see what I could use to prove this scientifically. What substance could I use to show the difference in volume measured one way verses another way while in Montana during the winter? Observe one cup of snow unpacked, one cup of snow packed and one cup of water all put into canning jars with lids on top to control evaporation:

One level cup of lose snow

One cup of packed snow

One cup of water

One cup each of lose snow on left, packed snow in the middle and water on the right

Observe the levels of the melted snow side by side, each was “one cup”

I would love to say that I was then able to measure out the melted snow precisely down to the fraction of a teaspoon (since a liquid cannot be compressed measuring by volume is fine). However, the sets of cute little hands I had helping me halted that scientific progress and since I could not accurately measure how much water spilled into the carpet I had to just use the visual you see in the last picture rather than try to repeat the experiment again.

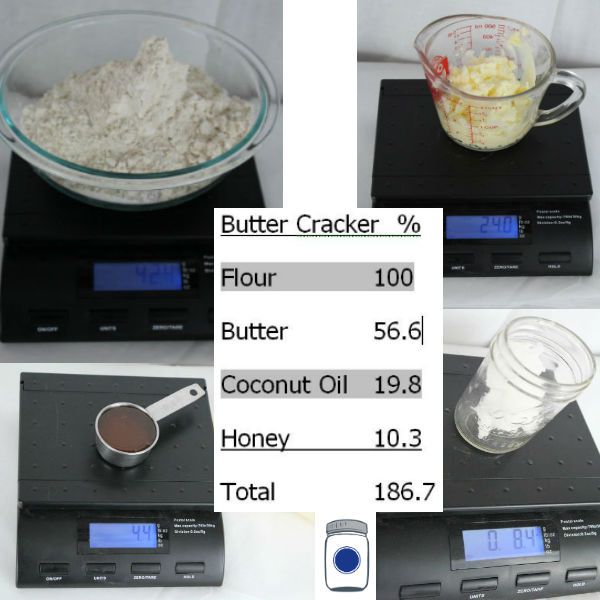

When baking with wheat, gluten is king and will determine what kind of product you are going to end up with. I put a handy gluten chart in this blog to show the proteins by percentage, in Europe they assign a number (i.e. #55 flour) that represents “ash content.” So what would a baker’s recipe (or formula is what it is called by the professionals) look like by weight? Chaya shows us here with this Butter Cracker formula:

The type of flour will drive the end product and ultimately the time scale portion of the baking math. The reason is because the more fiber and gluten in the flour the more water will be needed and the longer the dough will need to be baked.

As you see above, the Total Flour Weight (TFW if you needed one more acronym in your life) is 100%, because all other ingredients stand in ratio to that number.

If you got the hang of Total Flour Weight, then you can move on to Total Percentage (TP) which is a sum of the ratios. In baker’s math, a formula may call for a Total Percentage of 164 or 181 depending on the number of ingredients. The formula starts with 100 percent which is the sum of all flour (or flours if you are using more than one, they are simply combined).

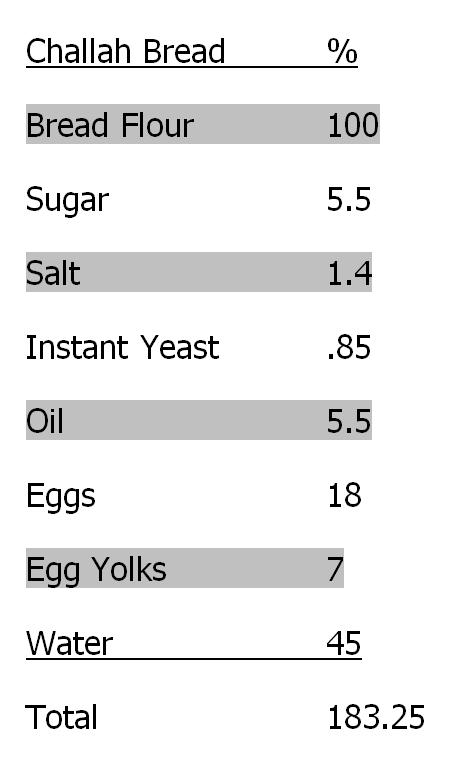

Take this example of Challah Bread as found on pp. 133-134 in Reinhart’s book:

You can see that the Total Flour Weight is 100 (as it should be) and the Total Percentage is 183.25 because the dough includes so many ingredients! Also of note is that the yeast to flour ratio here is .85 which means that the whipped eggs will be doing more work in this recipe—but more on that another day.

I will do my best to develop this further in later blogs, but for not suffice to say that baking math is more precise as everything is measured by weight and then stands in ratio to the only 100% ingredient which is the flour itself. The math in baking can take some getting used to at first, but you may find that you like it better in some ways and frustrating in others when it comes to the whole food ingredients you are using like salt or eggs. However, the precision and the probability that you can have repeatable results is really what makes this system the one used by the professionals.

Pro Deo et Patria,

Wilson

Works Cited:

Reinhart, P. (2002). The bread baker’s apprentice, mastering the art of extraordinary bread. (p. 27). Ten Speed Pr.

Photo credits:

All Photos by Pantry Paratus

Further Reading:

http://theinversecook.wordpress.com/2010/05/28/bakers-math-a-handful-of-practical-examples/

Wilson’s blogpost: The Expanded History of Baking Powder, Part I

Wilson’s blogpost: The Expanded History of Baking Powder, Part II

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.