Bleached flour, is that supposed to be refined?

Bleached or Unbleached flour—do I get the same results?

To better understand bleached flour we would do best to get to know the gradients of flour better. Sifting flour once makes it “clear”; sifting twice elevates it to “patent” (or “second clear”). People want the “clearest” flour they can find. According to Joel Salatin, all grain is actually very expensive and pretty much always has been through history before the age of cheap energy. If something becomes hard to get, it generally becomes more valuable; and what is considered more valuable is also associated with the appearance of wealth. The fact that societies even had grain at all was a sign of relative peace (no one was raiding or burning crops) and the presence of grain was a pretty good metric for prosperity (people had time and energy to plant instead of hunting and gathering).

The more flour is sifted the more “debris” is removed. What is left is endosperm or the pure starch and small amounts of protein (think fuel) for the wheat kernel to germinate from seed to plant. This process of discarding the roughage (the bran and germ portions of the wheat kernel) is an aberrant and abhorrent one, but has been around for centuries.

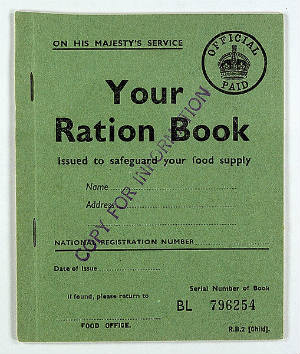

Early millers in Europe found that by passing flour though sieves of various sizes, the grain could be separated from its refuse, which made white flours the choice of priviledged classes (hence the term “refined”) and whole-grain flours the ingredient of peasants. . . . Interestingly, when white flour production was threatened during the Second World War, the British government outlawed white bread, replacing it with a rough whole-grain bread, nicknamed “the National Loaf.” Surprisingly, during a time of deprivation, the mean nutrition level improved, just the opposite of what would have been expected. (Joachim & Schloss, 2008)

Flour without the “debris” was considered more valuable even though it is not as healthy or filling. But to a baker, the quality of the flour is imperitive because flour “is called the ‘100 percent ingredient,’ against which all other ingredients stand in ratio” (Reinhart & Manville, 2002). The biggest factor in determining final baked product quality is the amount of protein in the flour. Although not exclusively gluten, for the sake of discussion we can say the “gluten content” of the flour is king.

Cake Flour: 6-7% Gluten

Pastry Flour: 7.5-9.5% Gluten

All-Purpose Flour: 9.5-11.5% Gluten *depends where it is grown and milled

Bread Flour: 11.5-13.5% Gluten

High-Gluten Flour: 13.5 to (rare but possible) 16% Gluten

Above chart attributed to (Reinhart & Manville, 2002)

Sometimes in Europe you see flour labeled as “#55” or “#65” which refers to the quality of the sifted final product which—again– will determine the outcome of the result of the baked goods. Most of us understand that the more heavier parts of the wheat kernel can weigh the flour down, making a light, fluffy texture difficult (not impossible, difficult). But all of that has to do with the granularity of the flour, what can we expect when we buy flour bleached? And here is another question you may have asked, “If you buy unbleached flour you may notice that it is slightly more expensive, why is that?” As it turns out, the color of the flour correlates with the thread count of the table cloth.

The whiter the flour the more valuable it was thought to be. If you have been following this blog, that makes about as much sense as a stripped down car selling for more than a fully loaded one, but I digress . . . Flour when it comes out of the grain mill is naturally yellowish as it boasts of the carotene pigments in the wheat berry that also correlate to the proportion of the gluten. Below you can see darker, hard red wheat on the left and hard white wheat on the right.

Millers and bakers knew that this process happened naturally.

If given half a chance, though, flour bleaches itself. That is, as it ages in contact with air, the pigments are oxidized and transformed into colorless compounds. But aging requires storage time, and time is money. That’s why “unbleached” —meaning naturally self-bleached during storage—flour costs more (Wolke & Parrish, 2005).

Historically, whole wheat flour was fermented. Time and bacteria did the work naturally and healthfully. But now the need was to have refined flour stripped, whitened and –by golly– this needed to be done expeditiously. After millennia of slow, healthy, whole food, the process needed some chemical accelerants. In 1774 a Swedish chemist named Carl Wilhelm Scheele isolated an element that was officially named Chlorine in 1810 by a British chemist named Sir Humphry Davy (Ettlinger, 2007). This new element was later pressed into service as an artificial aging agent.

Is there a measurable performance difference between bleached and unbleached flour?

Evidently there is:

The bleaching of flour isn’t mere cosmetics. Flour that has been matured, either by natural aging or by being treated with oxidizing agents, makes doughs that bakers report as being more elastic during kneading. That’s because oxidation not only removes the yellow color of flour but removes certain sulfur-containing chemicals (thiols) that interfere with the formation of gluten (Wolke & Parrish, 2005).

The bleaching process is pretty much assumed to have happened to store bought flour unless you see it labeled specifically as “unbleached flour.” This brings us to national security and the Department of Homeland Security’s interest in cake flour. No, seriously. Chlorine gas is very toxic, like banned in the Geneva Convention kind of toxic—so it has to be tightly controlled and transported in highly protected rail cars so that it does not get into the wrong hands. A separate danger is that flour is also very fine organic particulate that can be explosive under the right conditions and concentrations.

Chaya recently wrote an article about the effects of chlorine in water. If you think chlorine is benign enough to put in grandma’s cookies, think again.

And so there you have it, bleached flour was to accelerate the process that delivers us the finest of flours, cake flour. If you are playing along with the home game here, cake flour is stripped and artificially aged (bleached flour) so that it is the least nutritious least-likely-to-be-confused-with-healthy-bread, refined flour that you can buy. I think that I will stick with grinding my own flour in our grain mill.

Wilson

Pro Deo et Patria

Chaya’s Note: Although bakers who care more about aesthetics than health like to age their flours (or cheat and bleach them), aging your flour is a terrible idea! The extremely digestible nutrition of whole wheat is mostly found in oils. This even includes the iron, which oxidize with time and air exposure. Please use your home milled flour immediately—or put the rest in the freezer. If you want to use the oxidation process to lighten your flour, soak it in warm water before mixing in the other ingredients. This fermenting process will give you moister, lighter bread every time in a healthy way!

If you think you need sifted, all-purpose, bleached flour to get delicious and light results, think again. It takes practice, but you’ll get amazing artisan bread that will nourish your family by using the whole wheat! The picture below is of homemade Challah bread (traditional Jewish bread for Sabbath) using home-milled flour.

Proviso:

Nothing in this blog constitutes medical advice. You should consult your own physician before making any dietary changes. Statements in this blog may or may not be congruent with current USDA or FDA guidance.

Photo Credits:

Child’s Rations Book: The National Archives UK

All other photos are property of Pantry Paratus.

Works Cited:

Joachim, D., & Schloss, A. (2008). The science of good food. (p. 241). Toronto: Robert Rose.

Reinhart, P., & Manville, R. (2002). The bread baker\’s apprentice, mastering the art of extraordinary bread. (p. 29). Ten Speed Pr.

Ibid

Wolke, R. L., & Parrish, M. (2005). What einstein told his cook 2, the sequel : Further adventures in kitchen science. (1st ed. ed., p. 217). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

Ettlinger, S. (2007). Twinkie, deconstructed, my journey to discover how the ingredients found in processed foods are grown, mined (yes, mined), and manipulated into what a. (First printing,March 2007 ed., Vol. 1, p. 22). London: Hudson st Pr.

Wolke, R. L., & Parrish, M. (2005). What einstein told his cook 2, the sequel : Further adventures in kitchen science. (1st ed. ed., p. 217). New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Company.

UPDATE: While doing some research on FDA regulations regarding “Whole Wheat”, I came across this regulation about the bleach content found in wheat:

Unless such addition conceals damage or inferiority or makes the whole wheat flour appear to be better or of greater value than it is, the optional bleaching ingredient azodicarbonamide (complying with the requirements of 172.806 of this chapter, including the quantitative limit of not more than 45 parts per million) or chlorine dioxide, or chlorine, or a mixture of nitrosyl chloride and chlorine, may be added in a quantity not more than sufficient for bleaching and artificial aging effects.

You can find this on fda.gov with this identifying information:

| [Code of Federal Regulations] |

| [Title 21, Volume 2] |

| [Revised as of April 1, 2012] |

| [CITE: 21CFR137.200] |